The other day I was talking with a friend who does a lot of art writing. Gabby was nervous about a text she had just submitted to a “serious” art journal. Worried it was “too personal,” she anticipated disapproving notes from her editor, a VERY SERIOUS LADY. I get it—art writing is notoriously detached and prone to posturing—but I also felt a bit of, “REALLY, is this still a thing!? We still have to feel self-conscious about making work that’s “too personal?”

I had just finished reading Alison Bechdel’s Are You My Mother (2012), a totally shattering account of the artist’s relationship with her mom, heavy on childhood gay shame and told against the backdrop of psychoanalytic and feminist theory. In it, Bechdel reflects on beginning her career with Dykes to Watch out For (1987–2008), a comic strip that represented her world but was at arm’s length from autobiography. Later she transitioned to working on explicitly personal material through her memoirs about her mother and father (Fun Home, 2006). She credits this transition to the influence of Adrienne Rich:

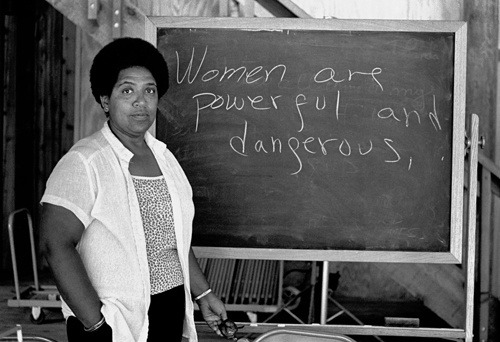

The question of “writing the self” is of course an old debate in feminist theory. Our French sisters—Cixous, Wittig, Kristeva, Irigaray—were all about l’écriture feminine, taking a poststructural approach to following the gendering of texts and language. American lesbian feminists like Audre Lorde and Rich told us about feminism by telling us about getting cancer, embodying the sting of racism, feeling ambivalent about the motherhood we’re supposed to love without question.

So if we already know all this stuff about women’s genres as bound up with autobiography, why the renewed interest in this debate right now? This is the question that’s been guiding a great deal of my reading over the last six months. I’m especially curious about framing this question in relation to media.

At the end of February I had the chance to help some super smart women—cheyanne turions and Hazel Meyer—throw together some readings for an iteration of the salon-style reading group, No Reading after the Internet, hosted on the occasion of Hazel’s exhibition No Theory No Cry at Art Metropole in Toronto. The centerpiece of the readings was Kate Zambreno’s “semiautobiography” Heroines (2012), a non-fictionish, experimental text that offers a speculative history of the wives of modernism—Zelda Fitzgerald, Vivienne Eliot, and others—set against Zambreno’s reflections on being the precariously employed academic wife of a tenure-stream research librarian. Zambreno writes with impunity about the necessary messiness of telling our stories; the body and the psyche figure prominently, and crying, sweating, avoiding the shower, getting our periods, or dealing with a rash are all valued epistemologies for communicating our emotional selves. Alongside Heroines we read selections from Ann Cvetkovich’s Depression: A Public Feeling (2012) and Sara Ahmed’s The Cultural Politics of Emotion (2004). The reading group took place at Art Met; we sat amongst the work and began the reading by listening to Hazel talk about her practice, which is very much engaged with these questions about thinking through the body, the messy self, and the inseparability of emotions and politics.

As a blogger—Heroines began as online writing—Zambreno is interested in how her access to a network of other feminist writers, and her own publishing platform less bound to ideologies of genre, alters the experience of being a woman artist, but also raises totally unresolved issues from modernism such as “what is the work? Who is the author?” (282). She writes:

“Online we negotiate and navigate what it means to be a writer, for some of us what it means to be a woman… . Yet of course many of us don’t write every day. That’s why I think of this form as a form of l’écriture feminine: a rhythm of silence and raw emotion, these fervent utterings… . A dialogue, a communication: the Internet. So intimate. These writings are the shudderings of the ego and lamenting the wound. We blubber and ooze. Texts that are raw, vulnerable, bodily and excessive. Sometimes freaking out in public. We are naked, like Karen Finley. My blog at times feels like a toilet bowl, a confessional, a field hospital” (286).

For the last couple months this blog has turned into a series of images about feminism and computing or the Internet. This is partly about me being too preoccupied to do much writing, but it’s also a way of reflecting on Zambreno’s suggestion that networked computing is a key moment for feminist modes of expression. Now that we write or make art online we are simultaneously freed up from the isolation imposed by the gendered political economy of print publishing or art criticism, but also acutely aware of how some of the problems faced by the ladies of modernism stay the same across media forms: for example, women’s work can now be dismissed because it’s “just on tumblr.”

Computers appear often in Bechdel’s reflections on her process in Are You My Mother. Bechdel at her desk working on a series of macs over a twenty-year period is a backdrop that’s easy to miss in the text because it’s so quotidian; but then attention to the ordinary is sort of key to this whole question about feminist genres.

On that note, I’ll end this with an image from Are You My Mother.

Feminist Computing #3: Alison Bechdel’s macbook pro with ergonomic stand: