Hazel Meyer and I have an article in the new issue of Little Joe. The publication is print only, but can be picked up at a range of art book stores, and if you’re in Toronto, there is a launch event at Art Metropole, January 16. Thanks to editors Sam Ashby and Jon Davies for inviting us to participate.

Hazel Meyer and I have an article in the new issue of Little Joe. The publication is print only, but can be picked up at a range of art book stores, and if you’re in Toronto, there is a launch event at Art Metropole, January 16. Thanks to editors Sam Ashby and Jon Davies for inviting us to participate.

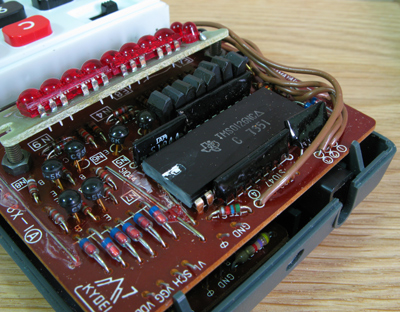

Hazel and I wrote about Tape Condition: degraded, an upcoming exhibition and series of programs we are organizing at the Canadian Lesbian and Gay Archives this summer. The exhibition is about the state of porn and other representations of sexuality on VHS tape in the CLGA’s collection, situated in the organization’s acrimonious history of police censorship of these materials. Through an immersive installation, publication, and a series of performances and talks, Tape Condition: degraded will invite the public to consider porn-on-tape’s status as a vital record of LGBTQ subcultures at a crossroads as community archives digitize their collections, seeking preservation and improving access. What happens to the boxes and boxes of porn as materials of more obvious “archival value”—materials like less controversial oral histories—jump to the front of the digitization queue?

The article is about our research process, which has involved a lot of reading, but also a lot of sorting through, watching, and rewinding old porn.

An excerpt:

To help the archives improve its catalogue records, we’ve been asked to assign descriptive tags to the videos we watch. From a pre-determined drop-down menu in the archives’ database we can choose from subjects like ‘lesbian’, ‘bareback’, and ‘leather’. This practice leads to a lot of conversations that sounds like this:

Cait: Is he wearing Rubber?

Hazel: I think it’s Latex.

Cait: Ok, but this is sort of Drag isn’t it?

Hazel: I don’t think something can be ‘sort of’ Drag.

Sometimes it’s hard to know what we’re looking at because these 25-year-old tapes have deteriorated, marked as such in the database with ‘Tape Condition: degraded’, from which we take our name. Colours have faded, there are occasional streaks and drop- outs, and there’s always the risk that a tape will snap when played for the first time in decades. This is especially true of the homemade tapes. While the estimated life of High Grade VHS tape stored at ideal temperature and humidity is thought to be 60 years, these particular tapes have been kept in basements, garages, or hot apartments in their pre-archives’ lives. Digital files efface the materiality of tape by promising to separate content from cassette, but the research we’re doing in this collection is steeped in the physicality of VHS: we rifle through boxes and handle cassettes, sliding them in and out of their cardboard sleeves. We squint to read labels and play ambiguous tapes in the hope of finding the kind of videos we seek. Our favourite tapes are the homemade collages of dubbed clips.

Drawing by Hazel Meyer, 2015.